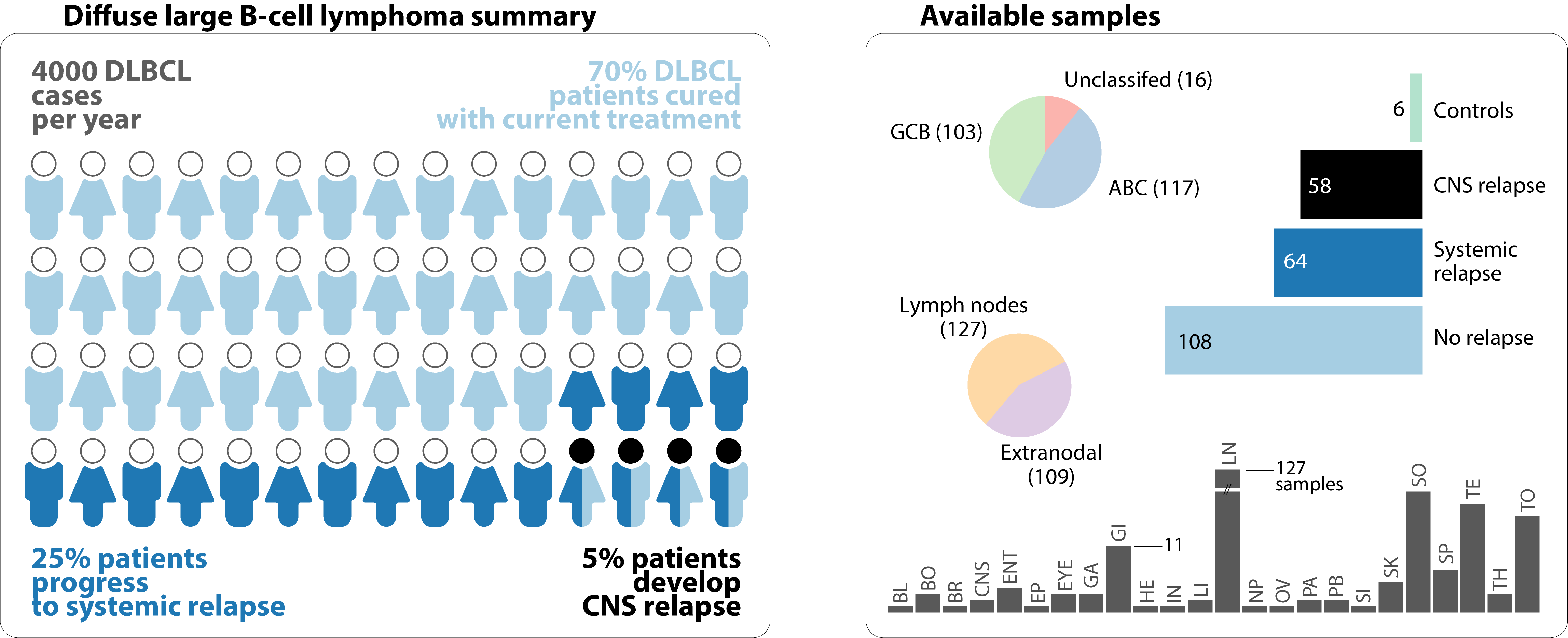

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) encompasses over 30% of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases, which make it the most common subtype with more than 4000 new cases a year in Canada. Using modern immunochemotherapies, more than 70% of patients are cured. The remainders are either refractory to the first line of the regimen or relapse after treatment.

The treatment is based on synthetic and organic compounds like anthracyclines and antibodies against CD20. Anthracyclines are synthesized from bacteria, specifically Streptomyces. They are used in wide range of regimens across many cancers, including leukemia and lymphoma. The effectiveness of these compounds comes with the burden of higher toxicity, causing wide range of cardiotoxicity and neurotoxicity. Anthracyclines, target DNA/RNA synthesis and cause cell cycle interruption. They disrupt the function of topoisomerases that relax the chromatine and make it accessible to the replication and transcription machinery of the cell. Whereas toxicity can affect tissue micro-environments, it can be an indirect cause of intra-cellular damage. For this reason, anthracyclines also promote cells increase of free oxygen radicals. These radicals disrupt histone configuration and cause direct DNA damage.

These immunochemotherapies are effective because they are designed for one purpose, cell destruction. Although effective, the elimination of all tumor cells in the body is not guaranteed. Remaining tumor cells, under new micro-environmental toxic conditions, change behavior and evolve dramatically to a more aggressive states. These new states can be qualified and properties estimated under new laws of clonal evolution. Only tumor cells with special gene signatures would survive under these therapeutic pressures. These signatures are quantified by the expression of genes. They represent the consequence of random DNA variants that increase the predisposition of a host to relapse and accrue more selective mutations. The latter favors the appearance of more aggressive tumors.

A certain 5% of individuals who relapse after treatment, develop on average 5 months from diagnosis, a central nervous system (CNS) relapse. This pathology is quickly and always fatal. At present, CNS prophylaxis exists and consists of agents with high CNS penetration. Treatment however is highly toxic to be administered early on and for the remaining individuals who are not cured.

Genetic risk factors for detecting relapse after chemotherapeutic administration can and must be identified. The left section of the visualization below represent a probabilistic number of individuals diagnosed with lymphoma in Canada each year. The right section shows a significant sample size of that Canadian population to be studied for genetic risk factors.